Empowered to Lead: Rethinking School Leadership Through Teacher-Led Models

What does this mean for the principal role?

Burnout and top-down mandates threaten to erode the heart of teaching; a quiet revolution is underway. Across the country, many schools are reimagining leadership by placing trust where it arguably belongs most: with the educators themselves. From fully teacher-led models to hybrid leadership roles, these approaches share a common belief—that those closest to students should have the power to shape the schools they serve.

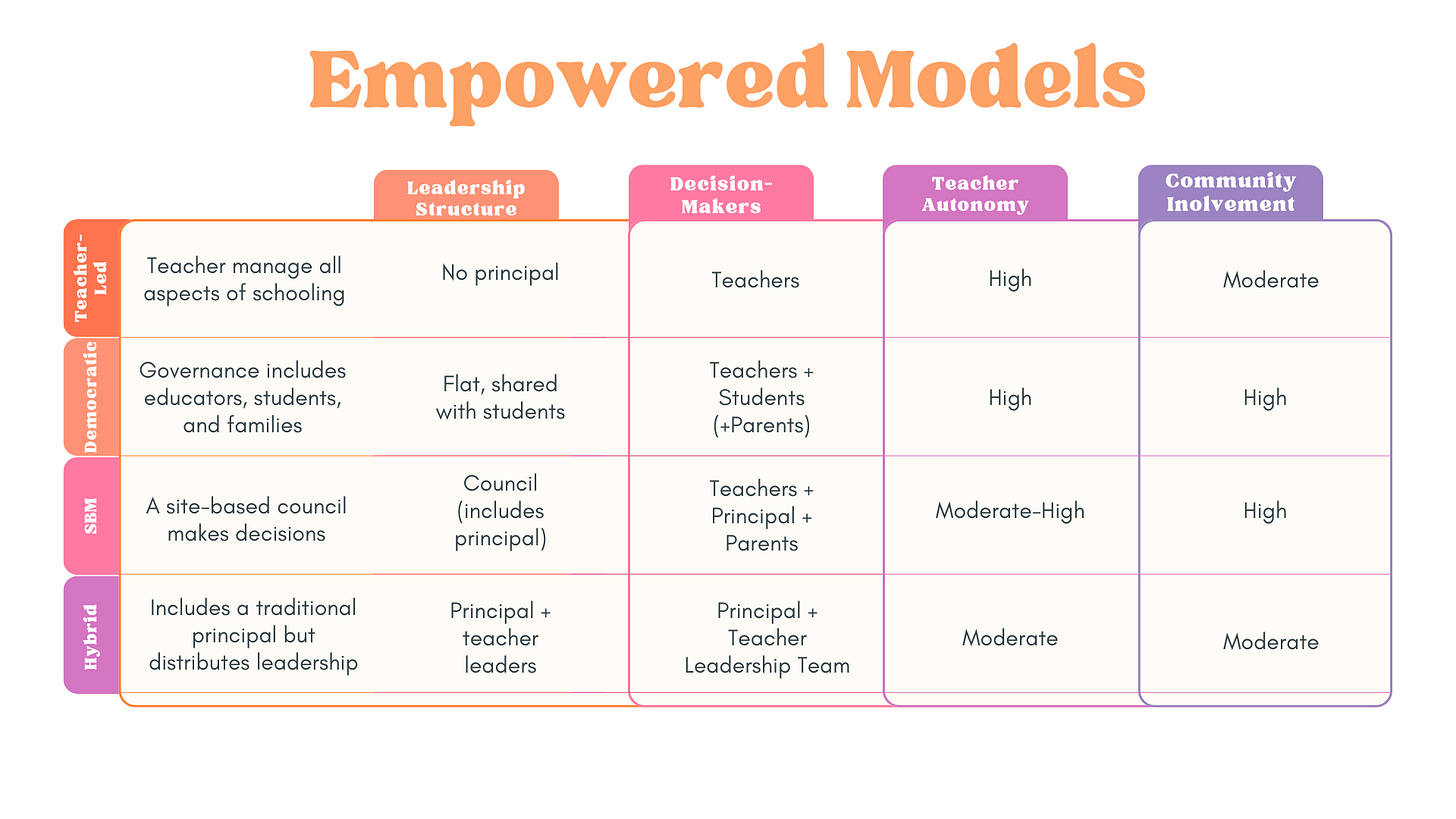

Four Models of Teacher Empowerment

1. Teacher-Led Schools

In these schools, there is no traditional principal. Instead, teachers collectively manage operations, curriculum, hiring, budgeting, and even peer evaluations. Leadership roles rotate or are decided through consensus.

Example: Howard C. Reiche Community School (Portland, Maine) Lead teachers lead evaluations, budgeting, and professional development, creating a school culture where leadership is a shared endeavor.

Benefits:

Deep ownership over school direction

High collaboration and trust

Decisions closely aligned with student needs

Challenges:

Time-consuming consensus processes can delay urgent decisions

Teacher workload and burnout can increase without traditional administrative roles

Mixed results in student achievement, with success often tied to strength of team dynamics and systems

Requires high relational trust and shared skillsets in leadership and operations

2. Democratic Schools

These models expand governance beyond educators to include students (and sometimes families), often through full-school voting processes.

Example: Sudbury Schools (Multiple locations) At Sudbury, staff and students have equal votes in all matters, including hiring and disciplinary policies. The belief is simple: everyone in the building should have a voice.

Benefits:

Promotes student agency and civic engagement

Reduces hierarchical power dynamics

Fosters collective responsibility

Challenges:

Student outcomes vary widely due to self-directed learning structures

May lack clear academic accountability systems

Teachers must manage facilitation more than instruction, which some find professionally limiting

Retention depends heavily on alignment with the school’s philosophy

3. School-Based Management (SBM)

A decentralized model where a site-based council—often made up of teachers, administrators, and parents—makes decisions about budgeting, staffing, and curriculum.

Example: Chicago Public Schools SBM Pilots Several Chicago schools have implemented SBM, empowering teacher voices in areas once controlled centrally with varying degrees of success.

Benefits:

Tailored decisions that reflect school-specific needs

Faster response to issues

Builds parent and community trust

Challenges:

Councils can become politicized or ineffective without clear governance training

Requires balance between autonomy and district accountability

Inconsistent implementation can lead to equity issues across schools

Teacher morale can drop if input is solicited but not acted upon

4. Hybrid Teacher Leadership

These models keep a principal but embed leadership deeply into teaching roles. Teachers serve as department chairs, instructional coaches, or innovation leads while maintaining some classroom responsibilities.

Example: Greenleaf Elementary (Oakland, California) Greenleaf K-8 adopted a hybrid leadership model that paired a strong principal with trained teacher leaders. Teachers remained in the classroom while taking on formal roles in instructional coaching, data analysis, and school improvement planning.

Benefits:

Leverages teacher expertise in systemic decisions

Creates growth opportunities without leaving the classroom

Supports distributed leadership alongside administrative vision

Challenges:

Teachers may lack time or capacity to lead effectively while teaching

Role clarity is essential to avoid confusion or duplication of effort

Success depends on a principal who actively fosters teacher leadership

Uneven professional development can hinder implementation

Shared Features of Empowered Models

Shared Governance — Decision-making is collective, transparent, and often consensus-based. Roles may rotate or be distributed by expertise.

Autonomy — Teachers design/refine curriculum, set assessment policies, and influence hiring, PD, and school-wide goals.

Community Voice — Parents and students are often engaged as partners in school governance, especially in democratic or SBM models.

Professional Judgment — These models trust teachers to make complex decisions, challenging the outdated notion that teaching and leadership are separate skill sets.

Challenges and Considerations

These models aren't without friction. Shared decision-making requires strong communication systems, clear accountability processes, and a deep well of relational trust. Without strong facilitation structures, decisions can stall or fragment. Teachers stepping into leadership roles need pedagogy, budgeting, hiring, facilitation, and policy navigation training.

A major caveat is capacity. Most schools are stretched thin. Curriculum design is one of the most complex undertakings in education—requiring deep content expertise, understanding of learning science, and equity-informed planning. When responsibility for such decisions is decentralized without adequate training and time, the result can be inconsistent quality and instructional drift. Our own biases and limited exposure to research-based curriculum design can unintentionally reproduce inequities.

Furthermore, while these models are often celebrated for innovation, the research on their effectiveness is limited—and in some cases, concerning. Some studies have shown that school performance has declined in schools that shift to teacher-led models without adequate support. Meanwhile, decades of research highlight that effective principals are among the most critical levers for student achievement, second only to teachers.

Distributed leadership is powerful—but not a substitute for instructional coherence and clear accountability.

Moreover, the best models don't reject the principal role; they redefine it. The most effective principals in these settings act more like orchestra conductors than solo performers—coordinating, supporting, and amplifying the leadership already present within their staff.

This week, I did an article analysis of leader-centric cultures, which sparked commentary of TikTok… and lead to this article you are currently reading:

Final Thoughts

The evolution toward teacher-led or teacher-empowered models doesn't mean the end of the principalship. It signals a rebalancing—a future where teachers are not just heard but heeded, where principals are not sole authorities but skilled facilitators of collective vision. Because when leadership is shared, so is the responsibility for what schools can become.

Schools don’t rise because of titles. They rise because of trust.