I know it when I start spiraling over the smallest thing—a signal to my brain screaming, "It's hopeless." I overcompensate, spinning out, trying to solve problems so massive they make the word problem feel almost laughable. Two years alcohol-free on Monday, but guess what? Still an alcoholic. Still caught in the all-or-nothing thinking. Still self-sabotaging. Still hiding in the shadows, hoping no one will notice when I inevitably stumble.

Maybe it’s because, deep down, I know the truth. Serenity—as we say—isn’t coming. Not for me. Not until every single kid gets what they deserve.

Crap.

But I’m a coach. I’ve been here before. I know how to get myself out of this, even when it feels like quicksand pulling me under.

Empowered women empower women - but what if they are disempowered?

I once received a gift from a work colleague that reads, “Empowered Women Empower Women.” I then started seeing this phrase everywhere: on stickers, pins, and notebooks. It spoke to me. It felt like the essence of my career.

School systems are the ultimate giant rubber band ball. One problem buried under another, wrapped so tightly in bureaucracy and pain, you can’t tell where to start. Even if you do find that first rubber band? Pull it wrong, and it snaps. Pull it right, and you’re left holding this fragile, stretched-out thing—creative tension.

Here’s the thing about creative tension. It’s supposed to keep us grounded, to drive us forward. But in education, that tension can tear you apart. Vision and reality stretch between two hands. On one hand, there’s the dream: equity, excellence, a system that works. On the other hand, there’s the ugly truth: a classroom full of trauma, a new initiative doomed to fail because no one has the time or energy to make it work. Pull too hard, and the band breaks. Keep it too loose, and it’s nothing but slack, spinning in circles.

We don’t talk enough about how f*cking painful the gap is between what we want and what we’re stuck with. Peter Senge calls it “creative tension,” but sometimes it feels more like despair. The creative gap isn't just something we live with—it's something that haunts us. We see the better version of ourselves, of our schools, of our students. Then we look at what we’ve managed to do, and it just... doesn’t measure up.

Mark Manson wrote, "The opposite of happiness isn’t sadness; it’s hopelessness.” That’s what we’re fighting against every day: Hopelessness. The weight of knowing you’ll never be able to fix it all.

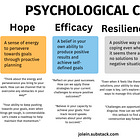

But here’s the paradox: hope is both the problem and the solution. It drives us to keep going, even when it hurts like hell and feels pointless. Hope gets us through the creative gap, past the frustration and failures, to the part where things make sense.

This work isn’t about “fixing” education—it’s about embracing the discomfort, the tension, the mess. It’s about knowing that the rubber band might snap, and doing it anyway. It’s about learning to love the stretch, the pull, the impossible balancing act between vision and reality.

Leaders, here’s your job: manage the tension. Don’t let the band break, and don’t let it go slack. Create spaces where teachers can fall short without feeling like failures. Celebrate the smallest victories, because sometimes those are all we have. And for f*ck’s sake, stop pretending like you have it all together. You don’t. None of us do.

This work is brutal. It’s exhausting. It’s a goddamn mess. But it’s also worth it. Not because we’ll ever make things perfect, but because every now and then, we get it right. We close the gap. We stretch the rubber band just enough to feel the snap of progress.

So yeah, it’s all f*cked up. But we’re still here, still pulling, still hoping. And that’s enough.

Read also:

This really spoke to me today. I'm retired from teaching science to pregnant and parenting girls (Broken Arrow, OK). There was tension every single day between students' body changes (feeling sick or exhausted), learning how to parent, boyfriend trauma, fighting social disdain for their pregnancy, and learning about cell division or atomic structure. Many days, it felt like nothing I tried to teach made sense to them. I often felt I'd failed. But when I learned to respect their priorities and acknowledge their challenges outside the classroom, I felt more effective. Thank you for sharing this perspective.